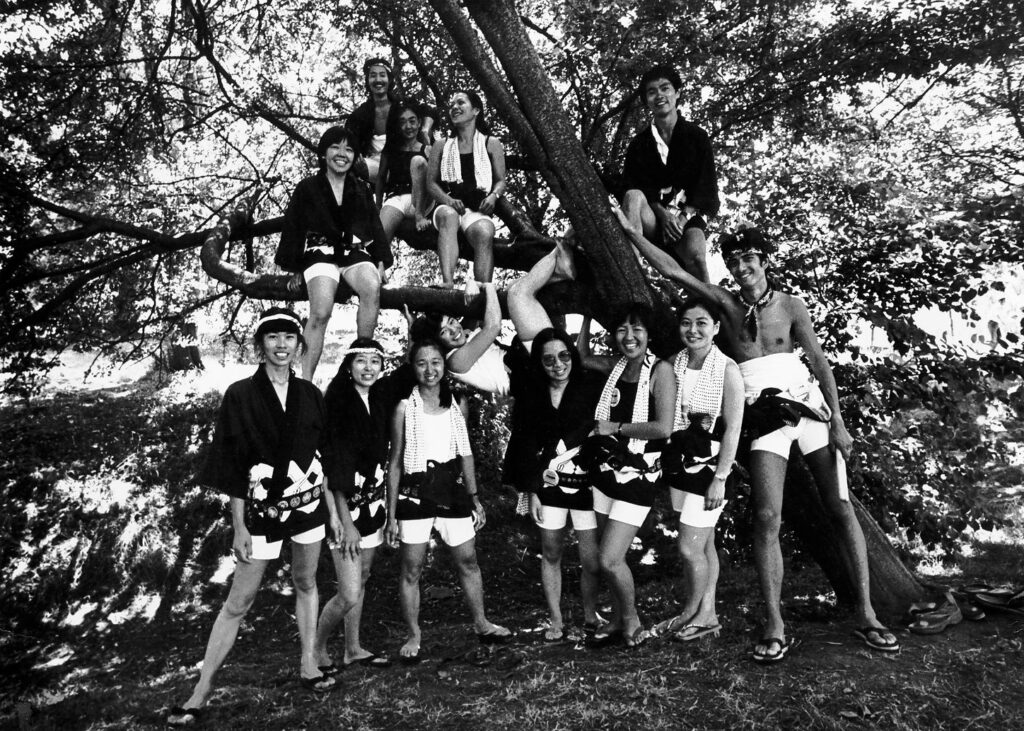

This is a talk I gave at Katari Taiko’s 40th Anniversary event at the Vancouver Japanese Language School & Japanese Hall.

November 2019

This is my version of the beginnings of Katari Taiko and the birth of Canadian taiko.

Canadian taiko was conceived in 1979 at the third annual Powell Street Festival, in Oppenheimer Park, a few blocks from here. Powell Street, home to the prewar Japanese Canadian community. Oppenheimer Park, home to the fabled Asahi baseball team, our very own field of dreams.

On that day, on that field of dreams, under a west coast sky, the earth opened up beneath our feet. With their first beat, their first kiai, the San Jose Taiko Group showed us a way. I was going to say a way forward, but it was not that. It was simply a way. A way to look both forward and backward at the same time. A way to look both inward and outward.

Taiko. The way of the drum. A way to summon music from thunder. A way to express who we were, as children of the children of those who worked the sea and the fields – the dispossessed, the interned, the maligned. The strong. This was music that you put your back into, that rose up through the earth, through the hara. It was an exhalation of breath, a meditation, an exultation. It was the sound of gambare – persistence; of gaman – endurance.

40 years and three months ago. And I remember it like it was yesterday.

If the conception was easy, the birth of Canadian taiko was not. To say we had no idea what we were doing would be a gross understatement.

But there was a will. So we found a way. We were the posterchild for a community-based, grassroots DIY project. Mayu’s parents were members of the Steveston Buddhist Temple, so we could practice there. We had broom sticks that we could saw into bachi. We had spare tires we could beat on in lieu of drums. Apart from that, we had nothing beyond our memories of that day in the park – a visceral energy that we were trying to recreate.

We needed help, and it would take too long for Youtube to be invented. That help arrived in the form of sensei Seiichi Tanaka of the San Francisco Taiko Dojo. He spent a week or so with us, attempting to mold us in his image. There was a little blood, a few tears, lots of blisters. He didn’t kill us, and I’m not sure he made us stronger, but he got us going.

Even then, we moved ahead in fits and starts. There was no plan. No blueprint. No leader. Some of the original members had no interest in performing in public. Our identity was forged in the crucible of the endless meeting. Hence our name. Katari. To talk. We would be a collective. Like San Jose. Consensus would be our queen. We would spend more time discussing the colour of our uniforms than we would our repertoire.

There was no magical, “ah ha, we got this” moment, no miraculous coming together of body, mind and spirit. Over time, though, we began to slowly gel. We were rough and we were ragged. But some kind of identity began to emerge. Our first public performance was in a mining town clinging to the side of a mountain in the Yukon. Once we began performing, audiences embraced us with open arms. With tears even. We began to compose our own pieces. Talking Drums. Freedom Taiko Dance. Oedo. Mountain Moving Day.

Our trip to Japan in the early eighties brought home to me how very Canadian our approach and our identity was – we didn’t have the steadfast intensity, or the discipline, of our Japanese forebearers. We didn’t play as one. We were a collection of individuals, playing together. Yes, the music we were playing had its beginnings in Hokkaido, Kyushu, Honshu, and before that, China; but it also had its roots in Rivers Inlet, Steveston, the Fraser Valley, Hastings Park, Tashme, Greenwood, Lemon Creek, Angler; in the rich and sometimes bitter soil of this country that we called home.

I’m sure that each of us, looking back, took something different away from those early years, those growing pains. I know that all of the members that flew the nest and created new groups had different visions and the groups are very different from the mother group, and from each other.

I think I speak for many of the original members when I say that the experience of forging Katari Taiko shifted the rhythms of our lives. The group was born in the aftermath of the Japanese Canadian Centennial, and in the leadup to the Redress movement. It was a seminal time, a wrenching time. A time of affirmation and exploration. As the community began to wake from those long and silent postwar years, we gave voice to some kind of wordless call to action, to remember, to honour those who paved the way for us, and to lay down a path for those who would follow.

The Japanese Canadian Centennial Project, A Dream of Riches, Tonari Gumi, The Powell Street Festival, Kokuho Rose – these all created the foundation upon which we built Canada’s first taiko group.

Just as the Japanese Canadian community took root on the west coast before fanning out across the country, so too did taiko gain a foothold here before spreading eastward. In Winnipeg, Edmonton, Toronto, Montreal . . . everywhere we touched down, taiko groups sprang up.

And here we are today. Bound together by this group, Katari Taiko, that birthed Canadian Taiko.

I was twenty when we formed Katari Taiko, the baby of the group. Today I am sixty. My two daughters play taiko. I met Amy through taiko, and we continue to play together. When I look at the contours of my life, I can see that, to paraphrase the book title, a rhythm runs through it. When I wake in the night and need to find sleep again, the drums begin in my head – don tsu don tsu doko don don don tsuko don tsu don tsu doko don don don – and then the chappa join in, bright and metallic, and then the shime daiko and then I drift off on a bed of rhythm. It works every time.

They say that in ancient Japan, the size of a village was determined by how far away one could hear the village drum. I’m not sure who “they” is, but it’s a compelling idea. And by that measure, we are members of a large village.

We were asked to present a work-in-progress, so we will be presenting two short pieces that somehow wove themselves together.

Taiko pieces tend to follow a certain structure, and while many of our pieces fit within that structure, we have been experimenting with a different, looser form.

There’s a quote from Tsong-kha-pa (Dzong-ka-ba), a Tibetan Buddhist, who talks about relaxing the effort, but without sacrificing the intensity. That quote came from Amy’s doctoral studies, and when I heard it for the first time, I thought, that’s it – that’s my philosophy of how taiko should be played. In our practices, we work on this concept through structured improvisations, or jams. The goal is to relax the effort, while sacrificing none of the intensity.

Bob Dylan once said, “The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on the Blonde on Blonde album. It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up.”

It always struck me as a beautiful way to describe that search for the music we hear in our heads. In Sansho, our practice includes experimenting with the sonic possibilities to find the right sounds. In that sense, all of our music is a work-in-progress.

The first piece we’re going to share with you tonight grew out of extended metal jams – not in the heavy metal sense, but playing the chappa, ascending gongs and singing bowl.

We rehearse at the Gold Buddha Monastery in east Vancouver, where Elaine and Cheryl are members. As part of the repentance ritual at the temple, the nuns chant the Offering of Flowers. The second piece is based on that chant.