cultural work

How did we get from “there” to “here” – from yellow peril to model minority, from the nail that sticks up gets hammered down to the squeaky wheel gets the grease?

Music was my entry-point into the Japanese Canadian community, first as a guitarist/songwriter with Kokuho Rose Prohibited in 1977, and then as a founding member of Katari Taiko, Canada’s first taiko group, in 1979. My ties to the community remain strong to this day, intertwined with many aspects of my life through family, work, food, and music.

taiko

In 1979 I was a founding member of Katari Taiko, Canada’s first taiko group. The group was seeded then nurtured in Oppenheimer Park (formerly Powell Grounds), the home field of the legendary pre-war Asahi baseball team. Oppenheimer Park sits in Paueru Gai (the Powell Street neighbourhood in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside), the former home to a thriving Japanese Canadian community before the wartime dispersal, incarceration, and dispossession of 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent.

The Powell Street Festival, first held in Oppenheimer Park in 1977 during the Japanese Canadian Centennial, became a nexus point for the post-war revitalization of the Japanese Canadian community. Katari Taiko, founded primarily by sansei, third generation Japanese Canadians, played a significant role in the rebirth of the community, inspiring the formation of taiko groups across the country.

In 1988, together with two other members of Katari Taiko, I formed Uzume Taiko, Canada’s first professional taiko group, with whom I toured and recorded for over ten years.

Today I continue to compose and perform taiko with Sansho Daiko, a group I helped form in 2010. In the reverberant pulse of the taiko I find a deep connection to the earth and to our ancestors, human and more-than-human, to an ancient and timeless vibration that moves through all things.

Here’s my version of the birth of Canadian taiko in a talk I gave at Katari Taiko’s 40th Anniversary event in 2019.

the bulletin

The Bulletin was founded in 1958 by young Japanese Canadians returning to the west coast after spending years in exile on the other side of the Rocky Mountains. Says founding editor Mickey Tanaka (née Nakashima) when I interviewed her in 2008, “Vancouver was beautiful, the returning Japanese Canadians were definitely optimistic, excited with their jobs, happy to be ‘home’ again. They started businesses, dry cleaners, gardening, florist shops, corner stores, barber shops, restaurants, garages, not only around Powell Street, but around the city. There were a number of school girls working and completing their education, boys enrolled in vocational schools. The JCs were scattered from Dunbar to Burnaby but gathered in places like the Maria Stella Club at the Sisters of Atonement social centre, or the United Church (where the Buddhist Temple now stands), or the Japanese Language School for community meetings.”

In 1993 I inherited the job of English-language editor of The Bulletin from my mother, Fumiko. Fumiko was among a group of activists who stacked an AGM and took over the board of the Great Vancouver JCCA in the lead up to Redress, thereby gaining control of The Bulletin and setting the stage for the magazine that exists to this day. I am the longest-serving editor in the history of the magazine and it continues to be a source of learning and community connection for me. I am honoured to carry on this important work, walking in the footsteps of nisei like my mother.

video

In recent years I have begun to delve deeper into what it means to be Japanese Canadian, to be part of a greater narrative stretching across generations. These videos come out of that process. They were created as Keynote presentations, then exported as videos. I love Keynote.

writing

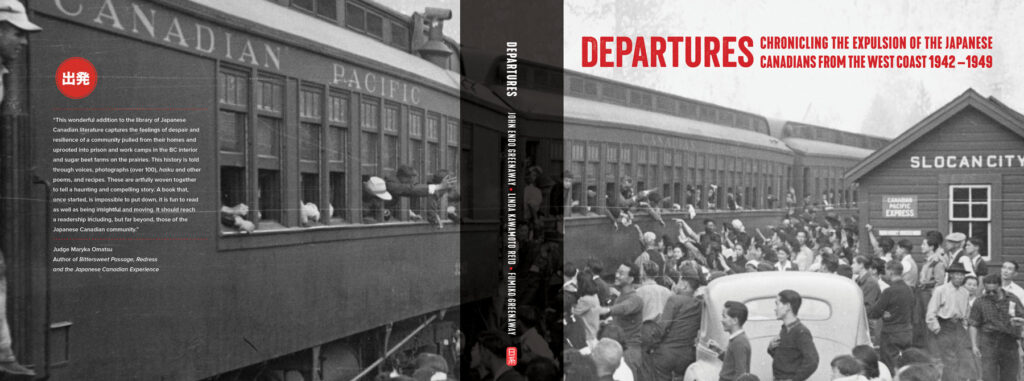

The germ of the idea that became the book Departures took root in the imagination of my mother, Fumiko Greenaway, in the early nineties. She had led several bus tours into the interior of the province, visiting the long-closed-down internment camps in the company of both younger participants and elders who had lived in the camps as children. Listening to the stories of those who had walked those hills and valleys, she saw the need for a publication that could serve as a self-guided tour book for those wishing to trace the footsteps of their parents and grandparents.

Following the historic Redress settlement in 1988, Fumiko and a partner received funding to publish a book but the project stalled out. My mother brought me on to finish the project, and while a final report was filed and the grant closed off, the book was never published.

When Fumiko passed away in Nelson in December 2011, the book remained an unfulfilled dream for her, something that has weighed on me until now.

In early 2017, I approached Sherri Kajiwara, Director/Curator of the Nikkei National Museum (NNM), with the aim of reimagining the book, bringing together images and memories, poetry, recipes, artifacts and artwork that evoke those years and those places, many of which are now lost to time, and soon, to memory. Rather than document the experience on a linear, factual level, the idea was to reach down into the essence of the experience – to get across as best we could what the people in the camps felt and ate and witnessed . . . and the poetry that it all elicited; not neccessarily to show the injustice of it all (although it was unjust), just to show what it was.

I also wanted to blend in some work and voices of the younger generations – my generation and beyond – to show the echoes of those years, how the internment experience continues to resonate today. Sometimes it is the echoes of silence.

Sherri agreed that the time was right for the book, greenlighting the project. Linda Kawamoto Reid agreed to come on board as co-author and we set about expanding both the size of the book and the content itself, delving deep into the NNM archives and pulling out new photos and new voices, as well as adding photographs of items from the collection.

I like to think that Fumiko would have approved of this finished book, as it carries on the spirit and intent of the original project while expanding on it with material that was not available at the time it was first envisioned.

Thanks to Sherri and Linda and everyone at the Museum who contributed suggestions and material as the book came together in its final form, making it, at long last, a reality.

My hope is that it touches the reader somehow, that it reaches something deep inside, where rivers run through, and the wind blows through – a beautiful, bountiful prison, “a part of Canadian history that cannot be suppressed.”