words

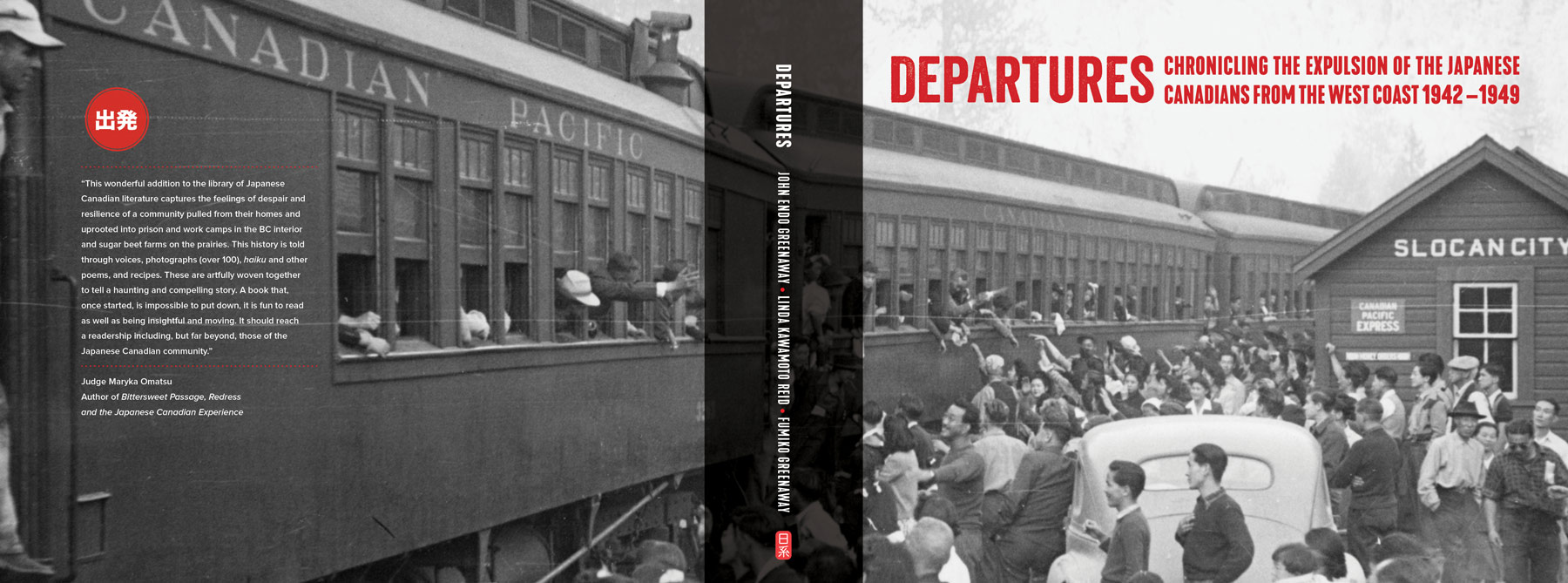

Departures: chronicling the expulsion of the Japanese Canadians from the west coast, 1942 – 1949

The germ of the idea that became this book took root in the imagination of my mother, Fumiko Greenaway, in the early nineties. She had led several bus tours into the interior of the province, visiting the long-closed-down internment camps in the company of both younger participants and elders who had lived in the camps as children. Listening to the stories of those who had walked those hills and valleys, she saw the need for a publication that could serve as a self-guided tour book for those wishing to trace the footsteps of their parents and grandparents. click to read more . . .

Fumiko herself had not been interned. Born in 1929, she was the eldest child of George Chohei Endo and Tomie Endo, formerly of Miyagi-ken, near Sendai, in northern Japan. A cook, George had come to Canada and followed the railroad east, finding a job with the CPR hotel in Moose Jaw. Setting down roots with his wife from an arranged marriage, they raised five children on the prairies. When the war came he lost his job and the family went on relief, but they were not forced from their home.

Moose Jaw was far from the hustle and bustle of Powell Street or Steveston, and Fumiko grew up isolated from other Japanese Canadians except for a few, like Tommy Shoyama, whom she knew as a teenager. Her first real exposure to other nisei came when the government set up a postwar dispersal centre in a former RCAF training facility on the outskirts of Moose Jaw for Nikkei moving east. It was her first taste of community.

Growing up, my mother had little interest in being a good nisei daughter, with the expectations and obligations that that entailed. With a lifelong desire to be an artist, Fumiko saved the money she made working as a bookkeeper/clerk at a Chinese grocery store and enrolled in art school, first in Regina and then in Philadelphia, where she received a scholarship to the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. When she returned to Canada she married my father, Tod, whom she had met a year earlier through her art teacher in Regina.

After living and working a few years in Canada, Tod and Fumiko relocated first to England (where my sister Rachel and I were born), then Montreal (where our brother Rafael was born) then Toronto, and finally, in 1969, to Vancouver, at the urging of their good friend and fellow artist Roy Kiyooka, who was also from Moose Jaw.

In Vancouver, Fumiko, now in her mid-forties, began to reconnect with the Japanese Canadian community. Living in a housing co-op in the Strathcona neighbourhood, artists and activists like Takeo Yamashiro and Tamio Wakayama were her new neighbours. It was, she said years later, like coming home.

In the mid-seventies, she heard that the Japanese Canadian Centennial Project was looking for a bookkeeper, and just like that she had found herself embedded in the Nikkei community, getting to know people like Roy Miki, Randy Enomoto, Linda Uyehara Hoffman and Michiko Sakata – sansei and shin-ijusha for the most part. From there she became involved in Tonari Gumi, and then the Redress movement. In 1984 she was among a group of activists who took over the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association and their monthly publication, The Bulletin, eventually becoming Managing Editor. With a keen interest in food and cooking, Fumiko started the Community Kitchen column in The Bulletin, which quickly became a favourite among readers.

Following the historic Redress settlement in 1988, Fumiko and a partner received funding to publish a book but the project stalled out. My mother brought me on to finish the project, and while a final report was filed and the grant closed off, the book was never published.

When Fumiko passed away in Nelson in December 2011, the book remained an unfulfilled dream for her, something that has weighed on me until now.

In early 2017, I approached Sherri Kajiwara, Director/Curator of the Nikkei National Museum (NNM), with the aim of reimagining the book, bringing together images and memories, poetry, recipes, artifacts and artwork that evoke those years and those places, many of which are now lost to time, and soon, to memory. Rather than document the experience on a linear, factual level, the idea was to reach down into the essence of the experience – to get across as best we could what the people in the camps felt and ate and witnessed . . . and the poetry that it all elicited; not neccessarily to show the injustice of it all (although it was unjust), just to show what it was.

I also wanted to blend in some work and voices of the younger generations – my generation and beyond – to show the echoes of those years, how the internment experience continues to resonate today. Sometimes it is the echoes of silence.

Sherri agreed that the time was right for the book, greenlighting the project. Linda Kawamoto Reid agreed to come on board as co-author and we set about expanding both the size of the book and the content itself, delving deep into the NNM archives and pulling out new photos and new voices, as well as adding photographs of items from the collection.

I like to think that Fumiko would have approved of this finished book, as it carries on the spirit and intent of the original project while expanding on it with material that was not available at the time it was first envisioned.

Thanks to Sherri and Linda and everyone at the Museum who contributed suggestions and material as the book came together in its final form, making it, at long last, a reality.

My hope is that it touches the reader somehow, that it reaches something deep inside, where rivers run through, and the wind blows through – a beautiful, bountiful prison, “a part of Canadian history that cannot be suppressed.”

say the names, say the names

after al purdy

like a gust of wind blowing in off the pacific,

over the strait,

the empty husks of Powell Street.

say the names

Hastings Park, the livestock buildings,

through the fallow fields of the Fraser Valley.

say the names

Beyond Hope.

Follow the Crowsnest east.

Say the names, half remembered:

Tashme, Greenwood,

Slocan, Lemon Creek.

say the names

New Denver, Sandon,

Kaslo, Lillooet,

Bridge River, Minto.

say the names

say the names

– John Endo Greenaway

The following poem/dream is by my father Tod from his self-published book, Behold! a closer look at what we see and do not see by dreamlight. This piece of writing resonates with me on some deep, subconscious level and I have used it in performances over the years.

the fading of the world . . .

I stood in an orchard or a wood

drenched in anguish.

The trees were hung with yellow catkins

from which an amber pollen drifted down

thick and slow,

a vertical blizzard.

Turning to look at it, backlit by the sun,

I saw that the flakes were thinner and whiter,

a dance of Brownian movement.

I saw all this, I saw the movement, the intricate structure of the falling grains,

but I remembered how much more intensely

I had seen this same phenomenon when I was a child.

At that time, the pollen – and by extension all phenomena –

had been tumescent, as you might say, with its own existentiality.

I tried to understand what we gain as compensation for such a loss.

I could not make out.

– Tod Greenaway

Last year I was walking down the trail from our place towards the inlet. It was dusk, the light rapidly fading. I came around a corner and was struck by the way a tree was glowing spectacularly in the fading light. When I got closer I saw what looked like clusters of glowing pods hanging from the branches. The setting sun was shining off them, causing them to glow. I realized at that moment that these must be the catkins from my father’s poem. I googled catkin on the spot and indeed, that’s what they were. I must have walked this trail hundreds of times and never noticed these trees before. It took the light hitting them just right to call them to my attention.

Tegami (a letter home)

14 days

kunimono

ju-yokka

the distance between

then and now

I have built your temples

built your shrines

with my own hands

with these hands

I have dreamed your dreams

I am dreaming still

Ima mo yume ja

14 days

kunimono

from shore to shining shore

shingetsu kara mangetsu

I stand at the mouth

of a great river

a great silver shining

all scales + salt + gasping mouths

forgive the bitterness

mou yuruseya

the bitter taste

row after roe after…

new moon to full

kunimono

shingetsu kara mangetsu

I have dreamed your dream

I am dreaming still

Ima mo yume ja

– John Endo Greenaway + Hiromi Goto

Gnomon

gnomon mmmmm

gnomon stands

alone

these parallel tracks recede beneath

a wreath of clouds

unbound un

tethered once I spied a bobcat

harangued by a bully of crows

heard before seen

man, if that cat could fly

we’d see a scattering then

a scattering of crows

gnomon knows these tracks these

trails

foxglove

purple clover

wild rose

Snakes in the long grass

Summoning the light in this winterspring

imprecations

sink beneath the weight of this oily sheen, this dark and moving surface

twigcrack underfoot beyond the reach of cityroar

black cap and nut hatch

a summons of sparrows

a bully of crows

a scattering of thoughts

in these long shadows

– John Endo Greenaway